“The Aeneid” as Propaganda

The Aeneid is a famous epic poem written by the Roman poet Virgil in the late first century BC. It was written during the reign of the first Roman emperor Augustus. The epic poem narrates the story of Aeneas, the legendary founding father of the Roman race. It is often considered propaganda (Quint 62). This article aims to demonstrate that Virgil and Augustus use the Aeneid as a propagandist tool (in all senses of the word “propaganda”) to promote the Augustan reign.

First off, it is important to examine the meaning of the word “propaganda” before deciding whether the Aeneid falls under this category. I propose trifurcating the meaning of “propaganda” into different senses: the first one being its etymologically original sense, the second one being the political sense without pejorative, and the third one being the modern political sense with pejorative.

The following discussion on the word “propaganda” itself attempts to show that the Aeneid by Virgil is propaganda in the first two senses of the word. Then the rest of the paper discussing the Aeneid itself seeks to demonstrate that Virgil’s work can also be considered propaganda with a negative connotation.

Etymologically speaking, “propaganda” is related to the verb “to propagate”, which means “to spread” something widely. Ultimately, the verb “to propagate” comes from the Latin verb “propago”, which basically also means the same thing. Linguistically speaking, “propaganda” can function as a gerundive in Latin, and it means “things that are to be propagated” (neuter nominative plural). According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, the word “propaganda” became a part of the English language through the Latin name of the “Congregation for promoting the faith”, a committee of cardinals established 1622 by Gregory XV to supervise foreign missions (Online Etymology Dictionary). In this sense, it functions as an ablative feminine gerundive. In the end, it simply means the dissemination of something in its most literal sense. Therefore, it would not be incorrect to say that the Aeneid is propaganda in the sense that it seeks to promote the grandeur of the Roman people. As a matter of fact, most other works of literature would also be propaganda in this sense, because writers almost always want to spread something.

However, the sense of the word “propaganda” has changed ever so slightly since around the time of the first world war. The Online Etymology Dictionary defines it as “dissemination of information intended to promote a political point of view”, originally not implying deliberate misleading. The difference between this sense and the first one is that this one is a political term. Virgil’s work praises the Roman ideal of pietas which the founder of the Roman race possessed. Besides, it praises the “Golden Age” of the Roman Empire. Therefore, the Aeneid is propaganda in this sense because it seeks to promote a political point of view, i.e., the greatness of the Roman Empire. Wes Callihan, the founder of Schola Classical Tutorials, expresses the same opinion in a mini-lecture uploaded by Roman Roads Media. He thinks that Virgil himself would say that the work indeed is propaganda. His explanation is that Virgil would have thought that the greatness and principles of the Roman should be known by other people; ergo, the Aeneid is propaganda.

Descriptivist semanticists would not agree to classify anything that ought to be disseminated as propaganda, since the common modern usage of the word contains in itself a negative connotation. In other words, propaganda is spreading information to promote a political point of view, even at the cost of misrepresenting information (thus the pejorative implication). It is also dangerous because propagandist literature endures much longer than other forms (Senn). The Aeneid can be considered propaganda in this sense. Quint says that Virgil radically rewrites Roman history, “placing the origins that legitimate Augustan rule farther and farther back in time, beyond history and prehistory” (Quint 62). What the following discussion sets out to show is how Virgil misleads people in order to benefit the emperor Augustus and also romanitas, the Roman way. Specifically, the scene of Aeneas’ journey to the underworld will be discussed in order to clearly show why it is the case.

As has been mentioned earlier, the Roman way of life, especially the virtue of pietas, is emphasized and praised in the Aeneid. Aeneas is portrayed as a hero with many laudable traits. For example, he is strong, he is a capable leader, he is able to sympathize with others. Most importantly, he is consistently described as a pious hero throughout the epic poem. Pietas (piety), for the Romans, is about revering the gods and family, and fulfilling one’s duties towards them.

Augustus sponsored Virgil to write the poem, and he was pleased that Virgil made it seem like Aeneas parallels Augustus himself. both Augustus and Aeneas are heroes, at least in the eyes of Augustus. They both had to go through hardships in order to bring peace to the Roman people. Augustus views Aeneas’ virtues as a depiction of himself as well. Therefore, he even urged Virgil to finish the poem about Aeneas, which he views as being about himself as well. “The Vita Servii (27) states specifically that the writing of the Aeneid had been undertaken at the express proposal of the emperor. […] It is recorded in the Vita Donati that Augustus was unreasonably impatient to have the poem sent to him in instalments as it came from the poet’s hand” (Avery 225). Therefore, both Augustus and Virgil are behind this propagandist work.

Avery even thinks that Virgil was under the pressure to write the poem the way Augustus wanted, thus not being satisfied with his own work. Avery says that Augustus was even convinced that it was risky to let Virgil have the manuscript within reach. (Avery 228). Thus, the poet was not able to change anything to the poem. Virgil hoped to have the manuscripts burned, but they remained after his death. In short, according to Avery’s arguments, it can be said that the Aeneid is indeed propaganda and that the one behind this propaganda is not actually the poet himself, but the patron.

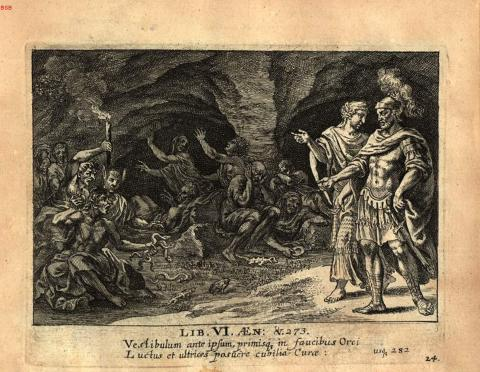

Last but not least, let us turn to discuss a specific scene in the Aeneid that also decidedly illustrates how the poem is political propaganda, which is Aeneas’ journey to the underworld in book VI. Virgil seems to blur the boundaries between mere historical accounts and legendary stories, merging them in such a way that makes legendary stories come closer to being real, and historical figures greater. He makes use of this part to glorify Augustus and Rome. Specifically, lines 1060 to 1085 are about the greatness of Caesar Augustus (Fitzgerald 187). Of course, the Romans were well aware that there were northern territories unconquered, let alone the eastern parts of Asia or southern parts of Africa. Yet, Virgil makes it sound like the whole universe was under Roman control: “Over far territories north and south / Of the zodiacal stars, the solar way, / Where Atlas, heaven-bearing, on his shoulder / Turns the night-sphere, studded with burning stars.” (188). Besides, Virgil (and probably also Augustus) judges that they were living during the Golden Age of Rome. The poem tries to convey the idea that it is a fact, not an opinion (line 1065). Judging whether a time period in history is the best or not usually is considered and agreed upon by later generations because contemporary people lack the wider historical perspective. Besides, the judgment is also an opinion, not a fact. Thus, asserting that Augustus brought Rome to a Golden Age is pure propaganda.

Given these points, the Aeneid was a propagandist work of literature. It was written by Virgil and sponsored by Augustus. These two figures then are the masterminds behind this propaganda. This article did not set out to belittle the literary quality of the work, but it has hopefully demonstrated that it is propaganda in all of the word’s senses. It is something to be spread widely; it is meant to spread a political point of view; and that it distorts history, as has been briefly described through the discussion of the underworld scene in book VI, thus also carrying a negative sense of the word “propaganda”.

Works Cited

Avery, William T. “Augustus and the ‘Aeneid.’” The Classical Journal, vol. 52, no. 5, 1957, pp. 225–229. JSTOR,

Bartsch, Shadi. “Ars and the Man: The Politics of Art in Virgil’s Aeneid.” Classical Philology, vol. 93, no. 4, 1998, pp. 322–342. JSTOR,

Callihan, Wes, lecturer. Is the Aeneid Propaganda? YouTube, YouTube, 18 Apr. 2016,

Eimmart, Georg C. Aeneas and the Sybil in the Underworld. 1688. Peplus virtutum Romanarum in Aenea Virgiliano eiusque rebus fortiter gestis, ad maiorem antiquitatis et rerum lucem, communi iuventutis sacratae bono, aere renitens, by G. J. Lang and G. C. Eimmart, Norimbergae : Sumptibus J.L. Buggelii, 1688, p. 24.

Homer. The Odyssey. Translated by Robert Fagles, Viking Penguin, 1997.

Homer., Robert Fagles, and Bernard Knox. The Iliad. New York, N.Y.: Penguin Books, 1998. Print.

“Propaganda.” Online Etymology Dictionary, Etymonline. Accessed 21 Apr. 2021.

Quint, David. Epic and Empire: Politics and Generic Form from Vergil to Milton. Princeton, 1993. Print.

Senn, Samantha. “All Propaganda Is Dangerous, but Some Are More Dangerous than Others: George Orwell and the Use of Literature as Propaganda.” Journal of Strategic Security, vol. 8, no. 3, 2015, pp. 149–161. JSTOR,

Virgil, , and Robert Fitzgerald. The Aeneid. New York: Vintage Books, 1990. Print.

Nguyễn Duy Thiên

“The Aeneid” as Propaganda – Vincentius Nguiēn Giaciemēnsis 阮唯天

vincentiusthien.wordpress.com