On the sculptural group “Laocoon and His Sons”

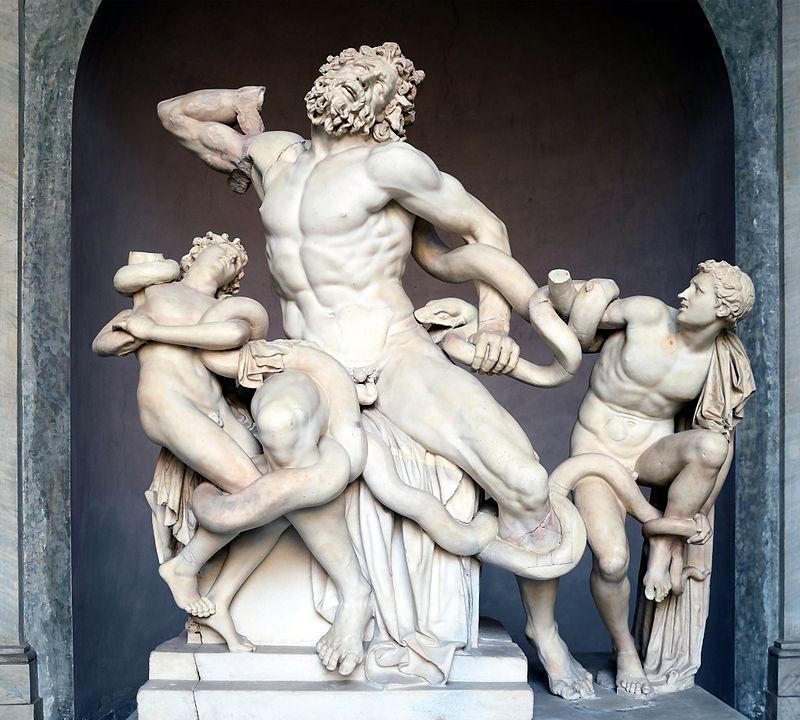

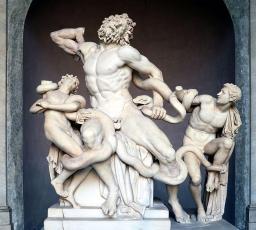

The sculptural group Laocoön and His Sons (figure 1) is a magnificent nobile opus that epitomizes Hellenistic art. Caius Plinius Secundus (also known as Plinius Maior, or Pliny the Elder in English), a notable learned Roman author, praises this statue in his Naturalis Historia (Natural History), book XXXVI. According to Plinius, there were three sculptors who made this statue: Agesander, Polydorus, and Athenodorus. The sculptors demonstrate artistic skills, turning the agonizing torment of Laocoön and his sons into an exquisite work of art.

Sculpture was one of the most important art forms of the Ancient Greeks: Sculptures served various purposes in private and public places. Throughout the history of Greek art, artists tried to perfect their craftsmanship, showcasing their best abilities, particularly through representations of human beings in sculptures. The sculptural group of Laocoön that we discuss here is from the Hellenistic period.

It was unearthed on 14th January 1506 in the vineyard of Felice de Fredis (near the Domus Aurea – Golden House – of the emperor Nero). The audience immediately appreciated the artwork upon seeing it (Squire 275). What we have today (figure 1) is a copy of an original. Paula Carabell mentions that Giovanni Cristoforo and Michelangelo, two leading sculptors of Rome at the time, concluded that the multi-figured group we have is not monolithic, i.e. ex uno lapide. Besides, we do not need to take their word for it because that is obvious from the studying the sculpture today at the Vatican Museum. As such, it is not the original because Plinius remarks: “Ex uno lapide eum et liberos draconumque […]” (From one piece of rock [the artists] made him (Laocoön) and the boys and the serpents […]). In other words, either the example we have today is a copy of the original, or Pliny was mistaken or using rhetorical language. Either way, the sculpture we have clearly exhibits all the attributes of a superb Hellenistic work of art.

Laocoön was a Trojan priest in the time of the Trojan War, whose death is described in the second book of the Aeneid by Publius Virgilius Maro. The Aeneid is the story about the Trojan hero Aeneas, who fled Troy (Ilium) after the Trojan War and became the ancestors of the Romans. In the second chapter of the book, Laocoön was mentioned as the chief priest of Neptune. According to John Lynch, Virgilius deliberately lingers on the description of the dialogue between Laocoön and Sinon in order to associate Laocoön with the old Republican Rome. Lynch even compares Laocoön to Cato Maior (Cato the Elder), who was a notable Roman senator: “Laocoön’s sweeping condemnation of the Greeks provides a most striking parallel to Cato’s well-known anti-Hellenic sentiments” (Lynch 172). “Quidquid id est, timeo Danaos et ferentis dona” (Whatever it is, I fear the Danaans even when they bring gifts). He distrusted the Greeks and warned the Trojans against the horse of the Greeks: “Equo ne credite, Teucri” (Trust not the horse, Teucrians). Laocoön’s words and deeds would have saved Troy, if not for the intervention of the gods favoring the Greeks, Aeneas argues. “Et si fata deum, si mens non fuisset laeva, impulerat foedare Argolicas latebras ferro, Troiaque nunc stares” (And if the fates of the gods, if our mind had not been on the left, i.e. tricked, [Laocoön] would have successfully persuaded us to destroy the Argives’ hiding places with a sword). Virgilius recounts in that same chapter the death of Laocoön. The Trojans thought that he was punished by the gods because he hit the horse. The sculptural group depicts the moment when the two snakes (angues/serpents) from the sea (pelago) strangle Laocoön and his two sons.

Indeed, the Laocoön group displays naturalism. Unlike the distorted and abstract human figures of the Geometric period, or the rigid quality of Archaic statues, or the idealistic Classical forms. The scale, size and proportions between the figures are proportional, that is, rendered in measurements true to natural forms. Artists also achieve naturalism by portraying all the subtle anatomical parts of the human body and how they correlate with one another and with the physical world itself. Laocoön has curly hair and beard, reflecting the hair style of the Hellenistic period. The follicles are of medium length since the curls fall to the side and to the back of his head. This shows the artists’ obvious ability to observe physical movement. Laocoön’s hair and beard are whipped with his head’s twisting movement and are pulled down by gravity at the same time. His sons have shorter hair, but they are no less affected by laws of gravity. The son on Laocoön’s right side has his head turned up and lightly to the side, allowing the artists to render his hair’s movement in space, demonstrating their evident interest in portraying what this scene would have appeared if it occurred in nature. Laocoön’s face shows signs of old age with wrinkles and saggy contracted muscles. In contrast, his two young sons’ faces, although they are also suffering, display fewer wrinkles as aging has not taken a toll on their youthful skins and muscles. Similarly, Laocoön’s body show his maturity in terms of physical age, whereas his sons’ bodies are not as fully matured. Maybe they have not even reached their puberty, as they do not have pubic hair like Laocoön. Nevertheless, Laocoön’s body still show he is a healthy and strong man. We see a lot of muscles and veins, as if Laocoön were an athlete who is training or has just finished his workout session. For example, we can see the veins in his left hand, connecting with his pectoral muscles. On his left side just below the arm, we can see his ribs under his muscles and veins. Both of his legs are not relaxed, although he is sitting on something. The proof is that there are veins popping out from his feet all the way up to his thighs. On the other hand, the figures are still naturalistic since we can almost feel like there is some fat under the fleshy-looking skins. Since Laocoön is sitting, the artists pay attention to making his belly look natural by making it look like there is some fat showing. The effect is also seen on his two sons, especially the one on his left side who is hunching over. Overall, the sculpture naturalistically presents a strong aged man and his two adolescent sons.

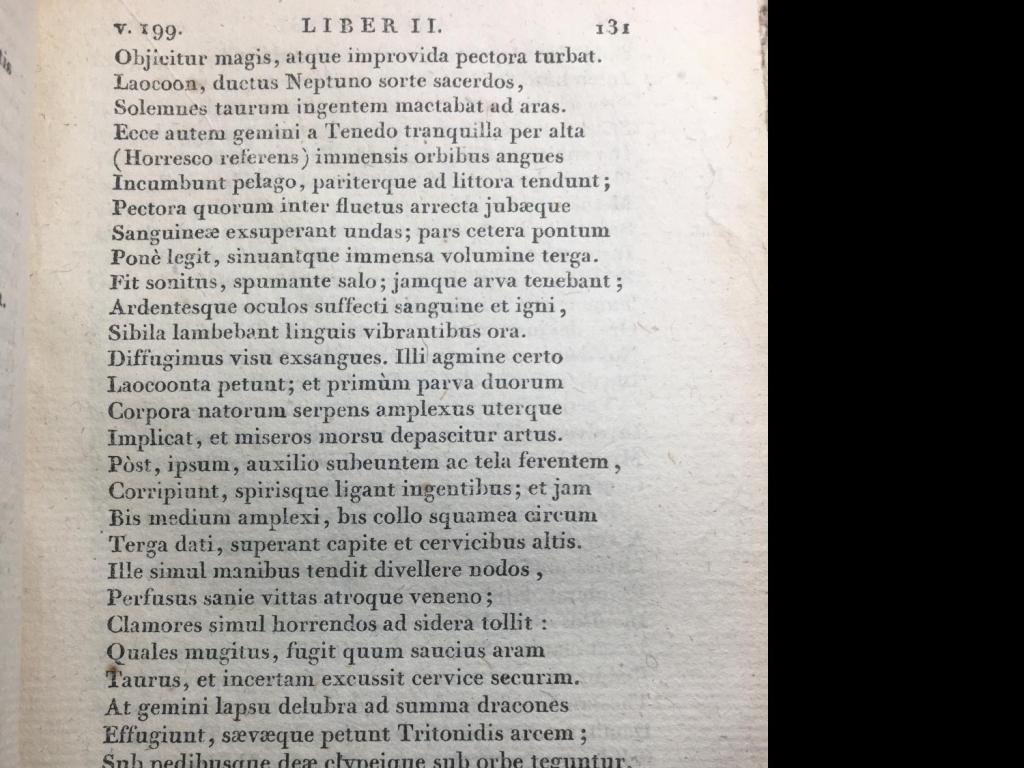

The physical representation is consistent with Virgilius’ description of Laocoön. In one passage, he mentions the pries’s swift and deliberate actions as well as his powerful and valiant speech. For instance, in verses 50-54 (according to the version I have, as shown in figure 2), Virgilius describes Laocoön’s action as followed: “Validis ingentem viribus hastam […] contorsit” ([…] He hurled a huge spear with his mighty strength). Apparently, he is described as a strong man in the original sense of Virgilius’ words. Furthermore, the usage of the plural form of the word for strength (in this particular sentence, it is in the ablative case: viribus) confirms that it is most frequently about physical strength.

In addition, naturalism also manifests in the clothing. The folds of the tunic reflect the interaction among the tunic itself, the three human figures, the serpents, and even the surrounding objects. For example, the fabric wraps around the left shoulder of the son on the left of Laocoön. It looks as if the cloth drapes down the young boy’s shoulder to his left thigh. The fabric under Laocoön flows under him and down to the stairs. The artists take great care in making multiple overlapping folds to create a sense of smoothness and softness of real cloth as well as repeating contour lines, creating a sense of rhythm.

The artists successfully make use of mass and volume to aid in creating a sense of depth and three-dimensional space. All the negative space between and around the figures are carefully carved in all directions, forming a vaccuum where the action takes place as though there were motional potential, particularly in these negative spaces. The volume of the figures and other objects take up space in our actual three dimensions, and so the artists make these figures appear alive in our real world. When light shines on the sculptures, it casts shadows, creating an effect called chiaroscuro. Chiaroscuro is the effect when an artwork displays dramatic contrasts between light and dark (as the name suggests), producing a sense of volume and dimension. As the sunlight moves above, the statue seems to move as well!

On the other hand, there seems to be no particular pattern or symmetry in the group. Rather, it is almost as if the artists wanted to let the figures interact among themselves, rendering actions, movements and composition all on their own. Consequently, the finished work looks very “organic” regarding shapes and composition. Having said that, the seemingly chaotic appearance reveals careful planning and visualization before and while the sculpture was made. There is pattern in the continuous lines of the folds of the drapery. Three human figures create a pattern. The contours of the hair curls create a pattern. Although it is asymmetrical, it is balanced.

Additionally, there is a lot of tension between opposite elements, making the artwork even more appealing. For example, the softness of the fabric and the hardness of the rock itself are opposite. It takes immense dexterous skills to turn something hard into something that appear so smooth and silky. In the same way, the rigidness of marble contrasts the twisting movements of the serpents and of the human figures. From an inanimate piece of rock, the artists made figures that look so alive and full of potential. These opposites are adeptly unified in a single artwork, inspiring awe in any audience.

Apparently, motion plays a huge part in this group. The style of these twisting figures was later called figura serpentinata, which is Italian for serpentine figure. This is similar to contrapposto, but the pose is more hyperbolic. As a result, the artwork looks more dynamic. Carabell holds that renowned sculptors of the past like Michelangelo was greatly influenced by this style of the Laocoön group. Jacques Bouquet even opines that the style figura serpentinata emerged in the early 16th century because of the Laocoön group. He, too, holds that the discovery of the Laocoön group profoundly impacted Michelangelo’s style. The ancient sculptors choose a specific moment in time where there is a lot of motional potential in the figures. As the name figura serpentinata suggests, Laocoön and his sons twist their bodies as if they too were serpentine!

Besides motion, emotion too is a major feature of the group. While Classical art is more concerned about religion, about the gods and idealized human proportions; Hellenistic art is more about human expression. Notably, this sculpture about Laocoön’s torturing anguish is a representative example. These are some of the nouns that some art theorists identify with Laocoön: “pain, marvel, death, madness, depression, desperation, nervous tension” (Loh 404). Loh even describes in her journal article that it is possible to hear Laocoön’s bitter cry.

Put in its historical context, the Laocoön group is categorized as Hellenistic art, although we do not know for sure the date. Assuming the sculpture in the house of Titus is the original, we know then that the material is marble. It probably served decorative purposes for the rich. It could have been commissioned by Titus. Indeed, Plinius mentions in book XXXVI of Naturalis Historia that he saw the sculpture in the house of the Emperor Titus ([…] in Titi imperatoris domo). Dimitris Damaskos, editor/writer of the chapter on free-standing and relief sculpture for the book A Companion to Greek Art, remarks: “From the Hellenistic period onwards the development of private commissions begins to acquire greater importance as compared with earlier times. Thus, many sculptures are thought to have been intended for decoration at wealthy houses in cities where numerous examples of contemporary buildings have survived, such as Delos or Priene” (123).

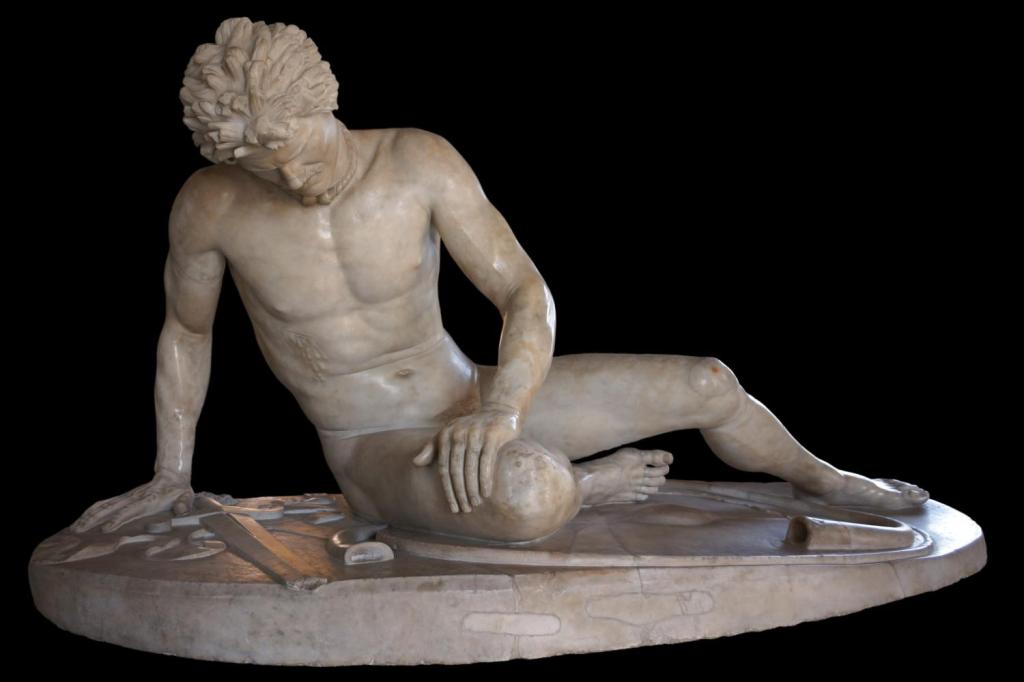

The Hellenistic period marks the beginning of the decline in the city-states. Consequently, large kingdoms with subjects of different ethnic backgrounds emerged from the once unified kingdom under Alexander the Great. Damaskos also asserts that the insecurity of the society and politics is expressed in the depictions of various new themes, including abstract concepts. Clearly, hyperbolic emotions are employed as well, as seen in numerous examples, such as the Laocoön group, the Dying Gaul (figure 4), and the Gaul committing suicide with his wife (figure 5).

In all of those three examples, the sculptors capture the moment before death of the main figures. The other two examples mentioned are two Roman copies of Hellenistic originals. They all exhibit a similar theme of suffering and death. The Dying Gaul depicts a man going through his pre-death moments. His mouth are slightly open, suggesting that he is moaning because of the pain. He turns his head down towards the direction of the mortal wound under his left chest, almost as if he has just tried to look at the injure to examine it as an instinct. Yet, he has given up. He has thrown down his weapon. His right hand can barely lift the weight of his moribund body. Similarly, the sculpture of the Gaul committing suicide captures the moment when he is killing himself. The tip of the sword has already penetrated his skin, and the blood is already pouring out. Death is coming, but in this particular moment the Gaul still has a lot of potential. His sunken belly indicates that he is taking a breath. This breath, plus his looking away, might have been served as a means of gathering courage to do the contrary to his instinct, which is killing himself. On his side, he still holds on to the lifeless body of his wife, whom he has just killed. This is a dramatic moment! Committing suicide is contrary to human instinct. Apart from death and pain, this sculpture also illustrates the unsettling decision and the distressful psychology of the figures.

Interestingly, the examples above do not show Greek heroes. Gauls were barbarians to the Greeks. Whether the Trojans were barbarians or not is hard to assert, but they were the enemies of the Greeks in the Trojan War! Again, Alexander’s empire was so big that it covered lands of people from different ethnic backgrounds. Consequently, this was reflected in the art.

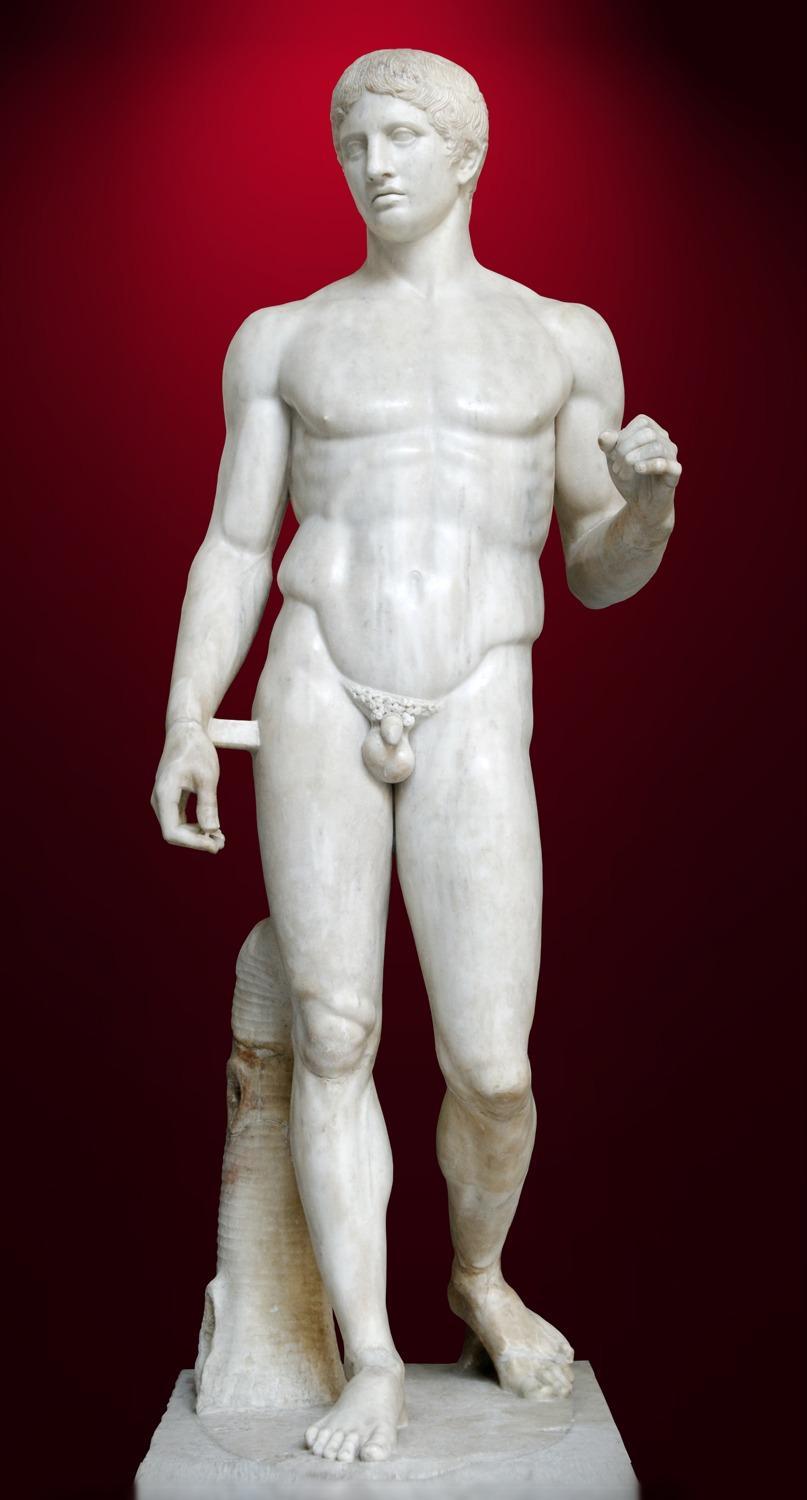

When compared with the art of the earlier times, e.g. Classical period, we see a shift in style and theme. The Doryphoros of Polykleitos depicts an idealized male figure (figure 3). It was clearly not an attempt at portraiture, so the Doryphoros possesses a generic look. Meanwhile, Laocoön is a specific individual. In the same way, the Gauls in figures 4 and 5 are more individualized. In addition, the Doryphoros is a hero: a strong and solidly-built Greek warrior. On the other hands, the other sculptures mentioned depict the death of non-Hellenes.

In any case, the Laocoön group was considered a masterpiece at the time. In book XXXIV, Plinius said “Cessavit deinde ars” (And then art ended) after talking about the art of the Classical period. As condemning as it sounds, he seems to contradict himself when he talks about the Laocoön group saying: “Opus omnibus et picturae, et statuariae artis praeponendum.” (A work that should be put before all other artworks of painting and of statuary). This praise is found in book XXXVI, which is not too far away from his own disparagement of post-Classical art in terms of book order! Either the Laocoön group made him change his mind, or he considered it an exceptional case for its excellence!

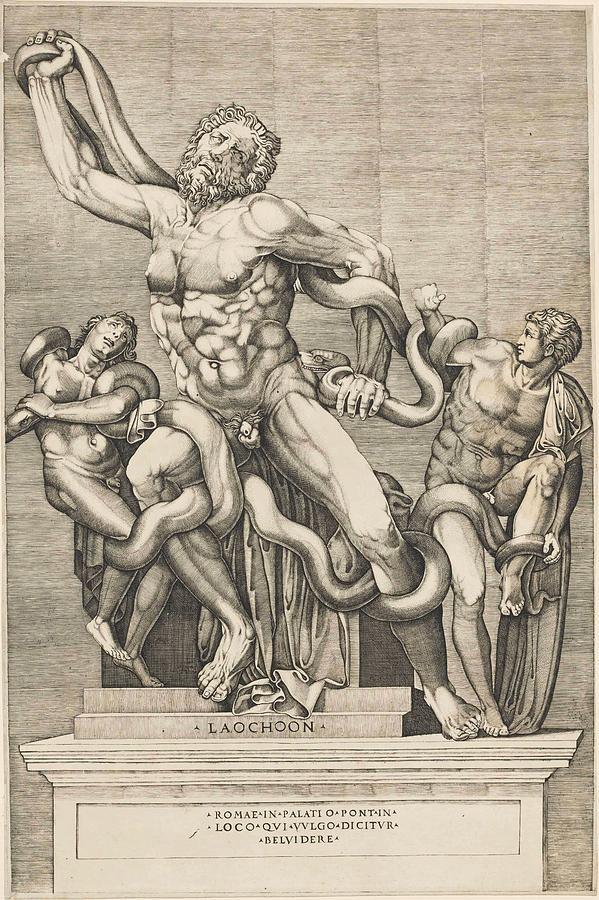

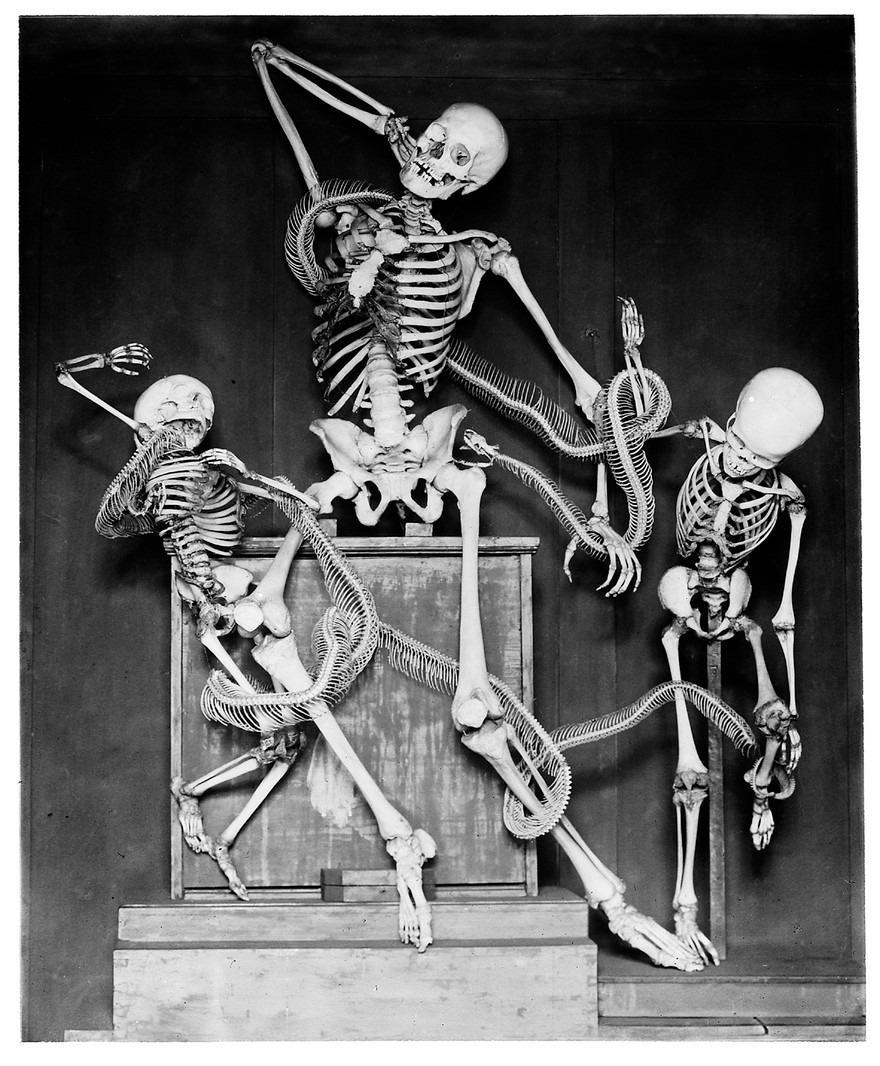

Furthermore, the Laocoön group has been and is still influential since its discovery in 1506. When it was discovered, it made an impact on Renaissance artists. The style figura serpentinata, as has been mentioned, was possibly initiated around that time. Many artists made engravings of it as well (as seen in figures 6 and 7). Many modern artists are still making art inspired by the Laocoön group (e.g. figure 8). The sculpture also influences other disciplines, such as poetry. For example, David Lear has a poem named “Laocoön” in his poetry collection. Matthew Arnold, a poet and critic, wrote a poem named “Epilogue to Lessing’s Laocoön”. There is another poem named “Laocoön” that was published in Echoes by Two Writers in Lahore in August 1884 with the sub-heading “Matthew Arnold”.

Given these points, the Laocoön group can be considered a timeless Hellenistic masterpiece. Plinius calls Agesander, Polydorus, and Athenodorus, who he claims made the sculpture, “the best artists” (summi artifices). The sculptors successfully turned a moment of pain and death into a work that can aesthetically convey motion and emotion. Definitely, the Laocoön group is a quintessential expression of the beauty of Hellenistic art!

_____

Images

Figure 1. Laocoön Group. Marble, copy after an original from ca. 200 BC. Vatican Museum, Vatican City.

Figure 2. Aeneis. Publius Virgilius Maro. Liber II, pagina 131. Parisiis : Excudebam Petrus Didot, natu major, Aedibus Palatinis Scientiarum et Artium. Anno Reip VI, 1798.

Figure 3. Doryphoros of Polykleitos in the Naples National Archaeological Museum. Material: marble. Height: 2.12 metres (6 feet 11 inches).

Figure 4. The Dying Gaul, or The Capitoline Gaul, a Roman marble copy of a Hellenistic work of the late 3rd century BCE Capitoline Museums, Rome

Figure 5. Ludovisi Gaul and his wife. Marble, Roman copy after an Hellenistic original from a monument built by Attalus I of Pergamon after his victory over Gauls, ca. 220 BC.

Figure 6. Laocoön. Copper engraving by Marco Dente, 1519.

Figure 7. Laocoön Group. Engraving by Nicolas Béatrizet

Figure 8. Josef Hyrtl’s skeletal arrangement of Laocoön (1924). Photographer unknown. Picture courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

_____

NB: All translations from Latin to English in this post are my own.\

_____

References

Arnold, Matthew. “Laocoön.” Poems – Laocoön, The Kipling Society,

Arnold, Matthew. The Poetical Works of Matthew Arnold. Thomas Y. Crowell & Company, 1897.

Bousquet, Jacques. Mannerism, the Painting and Style of the Late Renaissance. Braziller, 1964.

Carabell, Paula. “‘Figura Serpentinata’: Becoming over Being in Michelangelo’s Unfinished Works.” Artibus Et Historiae, vol. 35, no. 69, 2014, pp. 79–96.,

Lear, David. “Laocoön.” Poetry, vol. 46, no. 2, 1935, pp. 76–77.

Loh, Maria H. “Outscreaming the Laocoön: Sensation, Special Affects, and the Moving Image.” Oxford Art Journal, vol. 34, no. 3, 2011, pp. 393–414. JSTOR,

Lynch, John P. “Laocoön and Sinon: Virgil, ‘Aeneid’ 2.40-198.” Greece & Rome, vol. 27, no. 2, 1980, pp. 170–179. JSTOR,

Pedley, John Griffiths. Greek Art and Archaeology. 5th ed., Prentice-Hall, 2012.

Plinius, Caius. Caii Plinii Secundi Historiae Naturalis Ex Recensione I. Hardvini. Vol. 9, Augustae Taurinorum, 1833.

Smith, Tyler Jo, and Dimitris Plantzos. A Companion to Greek Art. John Wiley & Sons, 2012. Doherty Library.

Squire, Michael. “The Laocoön.” The Classical Review, vol. 60, no. 1, 2010, pp. 275–278.

Virgilius. Aeneis. Parisiis : Excudebam Petrus Didot, natu major, Aedibus Palatinis Scientiarum et Artium. Anno Reip VI, 1798.

hellenistic

,art

,art history

,laocoon

,research

,ngoại ngữ

Here's the link to my original blog post on Wordpress

Nguyễn Duy Thiên

Here's the link to my original blog post on Wordpress

On the sculptural group “Laocoön and His Sons” – Vincentius Annamensis NGUYỄN-Đinh Duy Thiên 阮丁唯天

nguyendinhduythien.wordpress.com